[/media-credit]

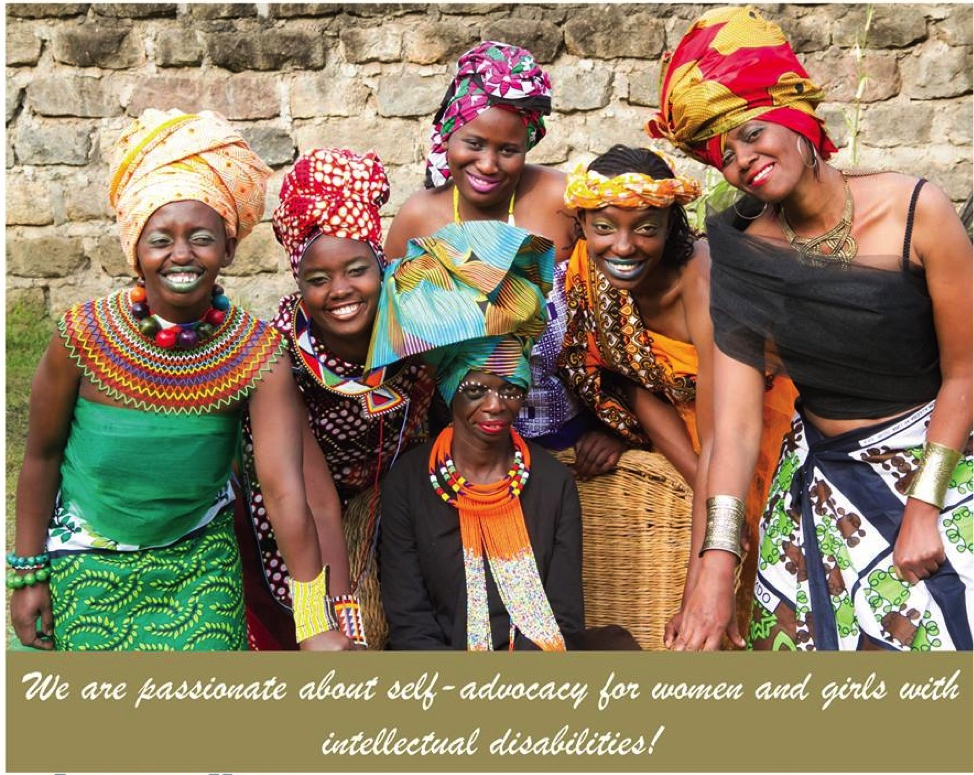

[/media-credit]Young women with intellectual disabilities dressed in colorful outfits

People with intellectual disabilities are people first — with desires, feelings, aspirations, hope, and dreams — just like any other person in society. Our disability should not be used to undermine us and deny us of opportunities and the desire to live a full life.

-Jane Akinyi, Disability Rights Fund Global Advisor and Self Advocate

Voices from our Global Advisors

In Africa, many children with intellectual disabilities are not even counted – denied a birth certificate and thus, an identity. They are often hidden and isolated in their houses, subject to verbal and even sexual abuse. Persons with intellectual disabilities are often considered useless and objects of pity with no chance for a life of dignity. Often believed to be a curse or a burden to a family, persons with intellectual disabilities around the world are excluded, shunned, and hidden from communities.

We decided to team up with advocates and experts to break down these stereotypes. In this story, Disability Rights Fund’s (DRF) Yumi Sera interviewed Jane Akinyi, DRF Global Advisor and Self Advocate from Kenya, and Fatma Haji of Inclusion Africa.

How can we facilitate empowerment of persons with intellectual disabilities?

We need to see life from their eyes, realize their potential, and provide them with opportunities. Respect, dignity, and choice are important values for persons with intellectual disabilities. According to Jane:

Many people fear or shy away from talking to us. One day someone visited our self advocates group and the initial questions she asked our support person were, “Are they violent? Will they understand when I talk to them?” I encourage people to interact with people with intellectual disabilities. That’s the best way to understand us and experience life from our lenses.

– Jane Akinyi

Self-advocates are persons with intellectual disabilities who can speak for themselves. They may also be trained to speak for their peers, who may have significant disabilities or communication difficulties or who may not have had the same opportunities and experiences to speak out.

How can we ensure persons with intellectual disabilities have support to make their own decisions and choices about their lives?

We need to recognize that persons with intellectual disabilities have diverse support needs in the decision-making process. For example, when you and I want to buy a house, we go to a financial advisor to give us support to make our own decision about our various financial options.

Similarly, a person with intellectual disabilities works on financial or health issues with a support person so that they have resources to make their own choices. As parents and adult caregivers, we should not act as their substitutes and make choices FOR them. In Africa, children with intellectual disabilities are told by their family members that they should not be heard, excluding them from the choices of what to wear, where to go to school, or even what to eat.

Supported decision making allows a person with intellectual disabilities to make decisions and choices on their own accord and according to their own needs. It promotes self-determination, control, and autonomy. It fosters independence.

Unlike substituted decision-making where guardians or family members or caregivers make decisions for the individual, supported decision-making enables the person to make his or her own decisions with assistance from a trusted network of families and supporters.

What are the challenges for persons with intellectual disabilities in Africa?

According to Inclusion Africa, persons with intellectual disabilities and their families are constantly confronted with staggering levels of unemployment, extreme poverty, inequality and exclusion. Issues of stigmatization, exclusion, and discrimination continue to be a major challenge. Notwithstanding the fact that some African Governments have signed and subsequently ratified the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD), most of the national disability laws being implemented in those countries are CRPD non-compliant and most critically, do not address Article 19 (Independent Living and Life in the Community).

Read about DRF-funded National Coalition’s work on Ghana’s first Inclusive Education Policy

In Africa there exists deeply rooted stigma and widely held discriminatory attitudes and myths towards persons with intellectual disabilities, which undermines many efforts to bring about change, both at the governmental and NGO levels. In many of our member countries, intellectual disabilities are attributed to spiritual matters or ‘juju’, and thus families known to have a child with an intellectual disability can be ostracized and feared. This drives the issue underground, so that babies and children with intellectual disabilities are hidden, locked in rooms, and denied access to health care and education. Sometimes these children are killed.

Due to this level of stigma, persons with intellectual disabilities are often invisible in the community and excluded from participation in the social, economic, and cultural life of their communities.

What do these challenges look like on the ground?

For example, in Kenya, families of children and adults with intellectual disabilities are often at a loss, lacking recognition and access to support services. A husband may abandon his wife who gives birth to a child with an intellectual disability because of the stigma from the community or because of superstitious beliefs. The mother, especially if she lives in poverty, is further ostracized from her neighbors, but must work to survive. This is the story of Mama Mary and her son Michael:

Mama Mary who is a mother of three children, one with an intellectual disability, who needs to earn a livelihood. She feels she has no options and certainly no access to support services. While she is away working, she locks up her autistic child Michael at home, leaving him tied to the furniture so he does not wander in the village to be taunted and abused by strangers or even raped or killed. If Michael is free to walk in town, he is at risk of being abused by merchants who order him to sweep or carry heavy loads. He is given a “job,” overworked, and seldom paid for his labor. So who do we blame here? Mama Mary for locking up Michael or the government for not providing support services for people like him? Communities often perceive families as villains, yet they don’t really understand the issues they are going through.

In places where special schools exist for persons with intellectual disabilities, most provide little instruction and few learning outcomes; the quality of education is poor. Public schools are underfunded and teachers are not trained to teach children with intellectual disabilities. On the other hand, private schools are very expensive; many families cannot afford to take their children there.

The other biggest challenge is that most of the adult learners with intellectual disabilities graduate after 20 years or more in school with no skills for the job market and no certification.

Things are slowly starting to change as governments are acknowledging that there is a group of learners with intellectual disabilities who are not benefiting at all in educational systems in Africa.

Inclusion Africa, and its member organizations of people with intellectual disabilities and their families, has started working with governments and giving guidance on how best to educate children with intellectual disabilities in mainstream and not segregated schools. Children with intellectual disabilities benefit more in inclusive schools: they make lasting friendship with their non-disabled peers and acquire more knowledge and skills.

What is one priority that needs to be changed?

Persons with intellectual disabilities are stripped of their legal capacity and seen as objects and not as subjects of the law. They are seldom counted and when they are, they are always among the last.

In many countries in Africa, persons with intellectual disabilities are not even recorded at birth – nobody knows about you, nobody recognizes you. They are denied rights as citizens – no birth certificate, no national identity card, and no voter registration card.

States must recognize that legal capacity is a basic human right. Legal capacity means that a person is recognized as a rights holder and has power to act according to their rights in a way that recognizes the need for individual and individualized support.

All other basic rights revolve around or are linked to legal capacity. The rights to health, political participation, marriage and children, and work all touch on issues of consent or contracts.

To me all the other rights are meaningless if I am not recognized as a person first. Legal capacity is about personhood—it’s about me.

– Jane Akinyi

When their legal capacity is recognized, children and adults with intellectual disabilities can start to exist and matter in the eyes of the law and the government. Parents can seek and demand services and proper instruction for their children.

With more support in their decision making and fulfillment of their dreams, adults with intellectual disabilities can live with dignity.

Jenipher ‘Jane’ Akinyi is a self advocate for persons with intellectual disabilities and a member of the Global Advisory Panel of the Disability Rights Fund. She is an active member of Inclusion Africa and Inclusion International. She continues to champion the rights of persons with intellectual disabilities with the goal of equal rights for all, including the rights to independent living and legal capacity.

Fatma Haji, Board member of Inclusion Africa, is a parent of a daughter with an intellectual disability and struggled with the inflexible infrastructures and mindsets in Kenya. She has made it her life’s mission to change these preconceptions in Africa.

Fatma Haji, Board member of Inclusion Africa, is a parent of a daughter with an intellectual disability and struggled with the inflexible infrastructures and mindsets in Kenya. She has made it her life’s mission to change these preconceptions in Africa.

Yumi Sera is the Director of Partnerships and Communications for the Disability Rights Fund. This story is part of a series of Voices from our Global Advisors.

Yumi Sera is the Director of Partnerships and Communications for the Disability Rights Fund. This story is part of a series of Voices from our Global Advisors.